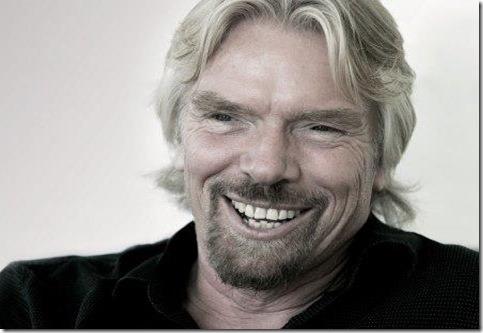

Born on July 18, 1950, in Surrey, England, Richard Branson struggled in school and dropped out at age 16—a decision that ultimately lead to the creation of Virgin Records. His entrepreneurial projects started in the music industry and expanded into other sectors making Branson a billionaire. His Virgin Group holds more than 200 companies. Branson is also known for his adventurous spirit and sporting achievements, including the unusual crossing oceans in a hot air balloon.

However, Richard is an extraordinary leader. He says that the one of the revelations he had is that he is able to inspire people and find the right team for his companies, making the main reason to hold more than 200 companies.

The crucial advice from Richard Branson was an amazing life-inspiring story shared in one of his books “Losing My Virginity”. He explains how his life depended on a couple of tasks he managed in his childhood by going out of the comfort zone.

“MY CHILDHOOD IS SOMETHING of a blur to me now, but there are several episodes that stand out. I do remember that my parents continually set us challenges. My mother was determined to make us independent.

When I was four years old, she stopped the car a few miles from our house and made me find my own way home across the fields. I got hopelessly lost. My youngest sister Vanessa’s earliest memory is being woken up in the dark one January morning because Mum had decided I should cycle to Bournemouth that day.

Mum packed some sandwiches and an apple and told me to find some water along the way. Bournemouth was fifty miles away from our home in Shamley Green, Surrey. I was under twelve, but Mum thought that it would teach me the importance of stamina and a sense of direction.

I remember setting off in the dark, and I have a vague recollection of staying the night with a relative. I have no idea how I found their house, or how I got back to Shamley Green the next day, but I do remember finally walking into the kitchen like a conquering hero, feeling tremendously proud of my marathon bike ride and expecting a huge welcome. ‘Well done, Ricky,’ Mum greeted me in the kitchen, where she was chopping onions. ‘Was that fun? Now, could you run along to the vicar’s? He’s got some logs he wants chopping and I told him that you’d be back any minute.’

Our challenges tended to be physical rather than academic, and soon we were setting them for ourselves. I have an early memory of learning how to swim. I was either four or five, and we had been on holiday in Devon with Dad’s sisters, Auntie Joyce and Aunt Wendy, and Wendy’s husband, Uncle Joe. I was particularly fond of Auntie Joyce, and at the beginning of the holiday she had bet me ten shillings that I couldn’t learn to swim by the end of the fortnight.

I spent hours in the sea trying to swim against the freezing-cold waves, but by the last day I still couldn’t do it. I just splashed along with one foot hopping on the bottom. I’d lunge forward and crash beneath the waves before spluttering up to the surface trying not to swallow the seawater. ‘Never mind, Ricky,’ Auntie Joyce said. ‘There’s always next year.’ But I was determined not to wait that long. Auntie Joyce had made me a bet, and I doubted that she would remember it the next year. On our last day we got up early, packed the cars and set out on the twelve-hour journey home. The roads were narrow; the cars were slow; and it was a hot day. Everyone wanted to get home. As we drove along I saw a river.

‘Daddy, can you stop the car, please?’ I said. This river was my last chance: I was sure that I could swim and win Auntie Joyce’s ten shillings. ‘Please stop!’ I shouted. Dad looked in the rear-view mirror, slowed down and pulled up on the grass verge. ‘What’s the matter?’ Aunt Wendy asked as we all piled out of the car. ‘Ricky’s seen the river down there,’ Mum said. ‘He wants to have a final go at swimming.’ ‘Don’t we want to get on and get home?’ Aunt Wendy complained. ‘It’s such a long drive.’ ‘Come on, Wendy. Let’s give the lad a chance,’ Auntie Joyce said. ‘After all, it’s my ten shillings.’ I pulled off my clothes and ran down to the riverbank in my underpants. I didn’t dare stop in case anyone changed their mind.

By the time I reached the water’s edge I was rather frightened. Out in the middle of the river, the water was flowing fast with a stream of bubbles dancing over the boulders. I found a part of the bank that had been trodden down by some cows, and waded out into the current. The mud squeezed up between my toes. I looked back. Uncle Joe and Aunt Wendy and Auntie Joyce, my parents and sister Lindi stood watching me, the ladies in floral dresses, the men in sports jackets and ties. Dad was lighting his pipe and looking utterly unconcerned; Mum was smiling her usual encouragement.

I braced myself and jumped forward against the current, but I immediately felt myself sinking, my legs slicing uselessly through the water. The current pushed me around, tore at my underpants and dragged me downstream. I couldn’t breathe and I swallowed water. I tried to reach up to the surface, but had nothing to push against. I kicked and writhed around but it was no help.

Then my foot found a stone and I pushed up hard. I came back above the surface and took a deep breath. The breath steadied me, and I relaxed. I had to win that ten shillings.

I kicked slowly, spread my arms, and found myself swimming across the surface. I was still bobbing up and down, but I suddenly felt released: I could swim. I didn’t care that the river was pulling me downstream. I swam triumphantly out into the middle of the current. Above the roar and bubble of the water I heard my family clapping and cheering. As I swam in a lopsided circle and came back to the riverbank some fifty yards below them, I saw Auntie Joyce fish in her huge black handbag for her purse. I crawled up out of the water, brushed through a patch of stinging nettles and ran up the bank. I may have been cold, muddy and stung by the nettles, but I could swim.

‘Here you are, Ricky,’ Auntie Joyce said. ‘Well done.’ I looked at the ten-shilling note in my hand. It was large, brown and crisp. I had never held that amount of money before: it seemed a fortune. ‘All right, everyone,’ Dad said. ‘On we go.’ It was then that I realized he too was dripping wet. He had lost his nerve and dived in after me. He gave me a massive hug.”

Branson’s words of wisdom and the courage of his parents by leaving him on his own since young age, made him powerful individual, leaving him with the experience of becoming one of the wealthiest person alive.

“You can always inspire by words.”